Do Neural Circuits Dedicated to Generating Sickness Behavior Contribute to Long COVID and Related Illnesses?

by Anthony Komaroff MD

Long COVID and ME/CFS

Following “recovery” from acute COVID-19, some patients develop a complex and debilitating chronic illness, often called Long COVID. The persisting symptoms include post-exertional malaise—fatigue and other symptoms made worse by physical or cognitive exertion—as well as unrefreshing sleep, cognitive impairment (problems with thinking, memory, etc.), and orthostatic intolerance (worsening symptoms when upright).

This illness resembles a similar disorder—myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)—that often develops following what appears at first to be just another acute “viral” infection. But unlike most such illnesses, this “flu-like” illness does not end. Patients often describe it as “a flu that never goes away.”

Long COVID and ME/CFS involve hundreds of millions of people, globally, and cause hundreds of billions of dollars in medical care costs and lost workforce productivity. Recent discoveries in neuroscience suggest underlying mechanisms that may explain the symptoms.

Post-acute infection syndromes

Neither Long COVID nor ME/CFS is unique. They are similar to illnesses that develop following other viral, bacterial and protozoal infections such as West Nile virus infection, post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome, and post-giardiasis syndrome. Recently, it has been proposed that all of these illnesses are examples of a category called post-acute infection syndromes (PAIS)12.

Underlying pathophysiology

Initially, it was unclear if any underlying biological abnormalities accompanied the symptoms of these illnesses. This led some physicians to dismiss patients seeking care for their symptoms. However, it now is clear that Long COVID and ME/CFS share not only similar symptoms but also a large number of similar abnormalities involving the central (CNS) and autonomic (ANS) nervous systems, the immune system, energy metabolism, redox imbalance, the gut microbiome, and the vascular system3.

From pathophysiology to symptoms

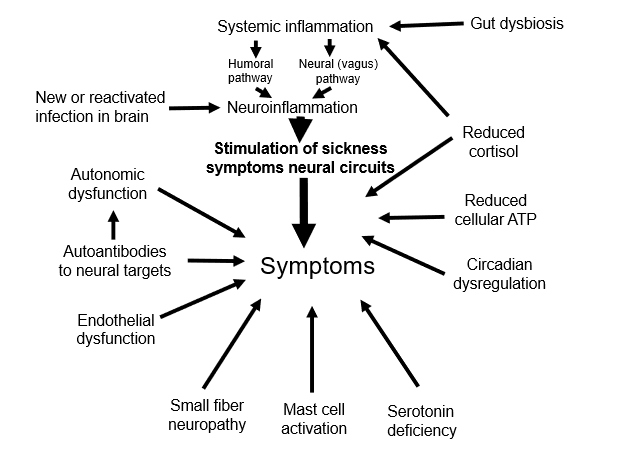

Understanding how this complex, multi-system underlying pathophysiology leads to the symptoms of the illness should lead to effective treatments. Clearly, some of the documented underlying abnormalities would seem capable of directly causing the symptoms through their effects on the brain. For example: 1) dysautonomia could reduce the flow of blood through the brain’s microcirculation; 2) endothelial vascular dysfunction could do the same; 3) autoantibodies targeting epitopes in the central and autonomic nervous system could plausibly affect cognition and autonomic function; 4) the impaired ability to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from glucose, fatty acids, amino acids and oxygen which has been documented could alter neuronal function.

Sickness symptoms and behavior

As a physician-scientist caring for people with ME/CFS, and studying the illness over the past 40 years, I was struck by the number of people who described the illness as “a flu that never goes away.” That raised two questions: 1) Why do we feel the way we do when we get the flu, and 2) Why, in some people, do these flu-like symptoms persist?

Pursuing the first question led me to discover the large literature on “sickness behavior”. It’s been known for decades that following experimentally-induced infection, humans and most animals studied (including fruit flies and worms) exhibit “sickness behavior”, including reduced activity of all sorts and reduced appetite. In humans, these behavioral changes clearly are in response to symptoms - we feel exhausted and we ache so we don’t move very much. We experience “brain fog” so we avoid cognitive challenges. We feel sleepy so we sleep. We have a poor appetite, so we don’t eat and digest. One can assume the same is true in other animals, even if they cannot articulate the symptoms. (If a parrot were to chirp that it was “tired and sleepy”, you wouldn’t believe it.)

At that time, 40 years ago, animal studies suggested that inflammation somehow triggered the behavior. Cytokines were being identified as molecular orchestrators of the inflammatory response, and recombinant DNA techniques were producing cytokines for use as therapeutics. Investigators reported that the infusions of cytokines were followed promptly by “flu-like” symptoms; then, when the infusion stopped, the symptoms promptly resolved. This supported the notion that sickness symptoms in humans were generated by molecules of inflammation.

Why has such “sickness behavior” following an infection been preserved by evolution throughout the animal kingdom? A plausible reason is this: sickness behaviors involve reductions in activities that consume ATP: movement, thinking, digesting, etc. By reducing energy-consuming behaviors, more ATP remains available to fight the infection and heal the injury caused by infection.

How would evolution have preserved sickness symptoms? In the past five years, in rodents, several neural circuits based in the hypothalamus and brainstem have been identified that appear to mediate sickness behavior. These neural circuits are triggered by molecules of inflammation, primarily cytokines and eicosanoids.

So, while specific infectious agents may be capable of generating certain symptoms more prominently than other infectious agents—such as the loss of taste and smell that can occur with SARS-CoV-2 infection in people with COVID-19—all infectious agents appear capable of generating a similar and stereotyped group of symptoms.

What triggers the neuroinflammation that then triggers the symptoms?

Neuroinflammation can result from infection of, or injury to, the CNS. In the past 20 years, it has become clear that inflammation outside of the brain, such as in the gut or lungs, can also trigger neuroinflammation—via blood-borne signals that penetrate the blood-brain barrier and retrograde neural signals that travel up the vagus nerve. There is considerable evidence in ME/CFS of smoldering low-grade inflammation in the gut caused by dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. In Long COVID, the immune response sometimes fails to fully eliminate the nucleic acids and antigens of SARS-CoV-2: they provoke an ongoing inflammatory response.

Summing it up

As shown in Figure 1, and summarized in detail in a recent publication4, many different underlying pathophysiological abnormalities can plausibly lead to some of the symptoms of Long COVID and ME/CFS. In addition, we argue that invocation of the sickness symptoms response may also be an important cause of the symptoms. Sickness symptoms and behavior in rodents appear to be generated by specific, dedicated, recently-discovered neural circuits. These circuits, and the neuroinflammation that activates them, suggest that targeting some aspect of neuroinflammation therefore may prove effective in reducing the symptoms.

Editor’s Note Dr. Komaroff’s guest blog explains that sickness itself is in the brain. Specific neural circuits in the autonomic nervous system literally control sickness symptoms including inactivity, loss of appetite, fever, etc. In my own experience with Long Covid, there have been no indications from blood and urine tests for immune system reactions even when I’ve been completely incapacitated by mold or other triggers, but there’s been clear evidence of autonomic nervous system dysregulation (e.g., dramatic uncontrolled changes in heart rate and blood pressure). So I suspect dysregulation of neural circuits that trigger sickness symptoms is responsible for my “crashes”. Dr. Komaroff is one of the world’s leading authorities on post-infectious illness and he describes here how he’s arrived at this critically important, but understudied, topic. -David Heeger

References

Choutka J, Jansari V, Hornig M, Iwasaki A. Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes. Nat Med. 2022;28(5):911–23.

Komaroff AL. Growing recognition of post-acute infection syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025;122(29):e2513877122.

Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. ME/CFS and Long COVID share similar symptoms and biological abnormalities: road map to the literature. Front Med. 2023;10:1187163.

Komaroff AL, Dantzer R. Causes of symptoms and symptom persistence in long COVID and myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome. Cell Rep Med. 2025;6(8):102259.